📝 Thanks for reading Fran Magazine, a biweekly blog by Fran Hoepfner (me). The way this works is that Wednesday (regular) issues are free for all and Sunday (dispatch) and reread diary issues are for paid subscribers only. Consider subscribing or upgrading your subscription for access to more Fran Magazine, and feel free to follow me on Instagram or Letterboxd.

Fran Magazine REMINDER

This is the last issue by me for the next few weeks! I am going to be away on residency in the Adirondacks working on writing that does not take place in Google docs. There are going to be three great guest posts and then I’ll be back with some nonsense about, I don’t know, Twisters?? Something we can all laugh about. There will be a Sunday Dispatch this weekend and then I’ll be jetting off. Thanks for reading! Don’t unsubscribe! I’ll come back, I promise!

The right side

Ever since I started teaching in 2019, I’ve maintained a very useful web-only subscription to The New Yorker which granted me access to lots of old good fiction to assign students and allowed me to keep up with the handful of articles that break through into the zeitgeist as well as a few favorite columnists (Janet Malcolm, of course, when she was there; David Grann in and out; Patrick Radden Keefe, Kathryn Schulz, Louisa Thomas, Doreen St. Felix, and a number of others). As someone who once let their print subscriptions to the magazine pile up in the corner of their dorm room, it’s been nice to keep up with something without seeing a physical reminder of what I’m behind on.

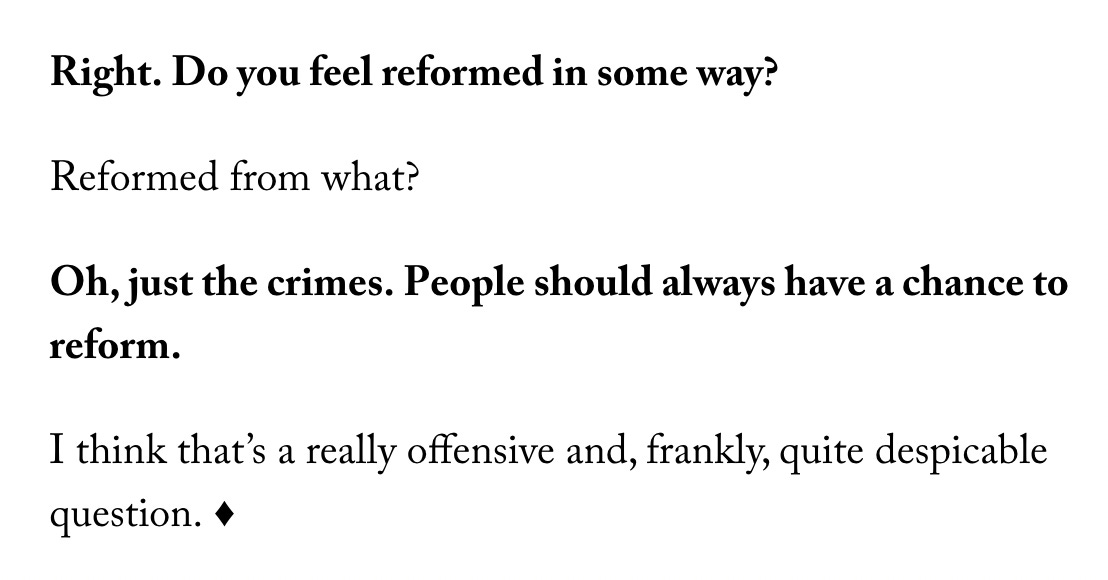

Since October 7th of last year, I have read Isaac Chotiner more regularly than usual, in part because he’s done many humanizing, informative interviews about the realities in Gaza. For those who are Fran Magazine readers but not Isaac Chotiner readers (funny overlap to imagine — for me, at least), he is a political and media writer who — while occasionally writing straight-forward columns — has become somewhat notorious for these hard-hitting Q&As with public figures who almost always wind up hanging themselves on their own words by talking to him. This happens with such a degree of frequency that people on Twitter will often joke that if they picked up the phone and it was Chotiner on the other line, they’d immediately hang up.1 Sometimes reading his work feels cathartic and illuminating — and tragic as the above linked interviews provide — and other times, I get weary of the journalistic class of individual “owning” the political public figure, who I think many of us have already come to accept as bullish, stupid, and uncaring. Don’t get me wrong. It’s occasionally satisfying to see people pivot into a frantic “I actually don’t remember what was happening,” but too much reading morally bankrupt people not knowing who they were morally bankrupt towards or when does feel like eating ten garlic knots in a row.

One of the most memorable of these interviews Chotiner has done in the past few months is with Elliott Abrams, a longtime state department figure who had his hands in Iran, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Chile, and now in Israel. A lot of parts of this very heated interview made the rounds online, particularly the end of the conversation, which is classic Chotiner.

It was another section of the interview, however, that I thought about when Phil and I watched the Costa-Gavras film Missing last night:

Missing is the third Costa-Gavras film I’ve seen — after State of Siege and Z — and like the other two films, it could be loosely categorized as a political thriller. For all that the label gets thrown around, I would argue that the pace of Costa-Gavras films is a little more loose and steadfast than “thrilling” — though no film is without its moments of excitement. Costa-Gavras is a Greek filmmaker who is bafflingly still alive — baffling both because he is in his 90s and also because he spent a significant chunk of the last half of the 20th century making films that are quite damning towards otherwise “good” nations, exposing political rot and conspiracy.

Missing is currently playing in the Criterion Collection series featuring movies with synth soundtracks; the very excellent score is by Vangelis who is probably known best to the Fran Magazine audience as the composer of the theme from Chariots of Fire. I am a little bit lol at a movie like Missing popping up in this collection, because while it’s not a wrong indicator of an interesting craft aspect of the film, the score is not even within the top ten things I am considering about the movie. Whatever it takes to get something on people’s radars!

Missing tells the true story of writer Charles Horman, a freelance writer, who went missing in Chile during the right-wing coup that occurred in the early 1970s. Horman was living in Chile with his wife; he worked odd jobs in journalism translation and the two of them were loosely left-wing in a “having a job is normal but I hate the government” type of way. Horman is played by John Shea (“Blair’s dad on Gossip Girl,” as Phil texted me this morning) and his wife Beth is played by the great Sissy Spacek. We catch a glimpse at their chill ex-pat life, hanging with journo pals and longtime friend Terry (Melanie Mayron2). As the situation in Chile starts to get increasingly violent, they start to make plans to leave. After a particularly stressful night in which Beth has to find her way back to their home, she realizes that their house has been ransacked and Charles is missing. Two weeks later, give or take, Charles’s father Ed, played by Jack Lemmon, flies out, and the two of them work together to try to determine what happened, the U.S. government giving them the runaround every step of the way.

It’s a very depressing film — it is clear, basically, from the jump (or the Wikipedia scroll, if you live like this) that the answer of “what happened to Charles Horman?” is “nothing good.” Though Costa-Gavras has made other films in English, he is not a Hollywood filmmaker — his films are too structurally loose and grim, far more concerned with idealogical honesty than “hitting beats.” The most conventional aspect of Missing is that Ed and Beth are on opposite sides of the political spectrum, and a number of their scenes together are him trying to reckon with her “kooky leftist views” that spit in the face of his conservative Christian Science. That Missing is helmed by one star from Old Hollywood (Lemmon) and one star from New Hollywood (Spacek) lends it an interesting air of legitimacy, so to speak.3 It’s not only that the horrible events of the film are happening, but they are happening to beloved Americans! The indignity! The injustice! The film goes so far to say as much just that near its conclusion, in which one of the sniveling U.S. diplomats says something to the effect that Lemmon’s Ed would not even care what the United States is doing in another country were he not personally involved.

I thought about Denis Johnson’s The Stars at Noon which I read a few weeks ago and the profoundly negative reaction to the Claire Denis adaptation of the film. I’ve made peace with the fact that many seem to dislike the film in part because Denis and her leads — Margaret Qualley and Joe Alwyn — are varying degrees of conversional figures because no one can agree on how talented or not they are.4 Set in Nicaragua, The Stars at Noon also depicts an unnamed female freelance writer and sex worker (played by Qualley in the film) who falls in with an English oil businessman (played by Alwyn in the film). These are unlikable characters taken on their own — frantic, stupid, petulant, frustrating. In a review of the novel at the time of its release, Caryn James described the female narrator as such:

With her religious imagery and taste for irony, her philosophical attitudes toward everything from her own prostitution to Managua's oppressive heat, it's not plausible that she could remain so willfully dazed. Mr. Johnson's first-rate soul-searching is trapped in her second-rate mind, which frequently borrows the author's eloquence and intellectual rigor.

Basically: how could a smart author write a character who knows references but also be stupid? Ms. James, have you heard of GRADUATE STUDENTS????

That the ostensible protagonists of The Stars at Noon are “unlikable” is apparent in the text, but especially in comparison to the Hormans who are classic good ally types: friends to locals, playing with children and pregnant women and other artsy people. It is easy to care about these white expats in over their heads when they are framed as good, though all these people are discarded in the same way. As Michiko Kakutani wrote on release:

Though such remarks supposedly belie a deeper vulnerability and pain, we grow so sick of this woman's posturing, so weary of her self-pity and tattered cynicism that we just want her story to end. We never really care whether or not she betrays her lover, and we certainly never care what eventually happens to her.

Both the Horman family and the female narrator in The Stars at Noon are undone through a series of runarounds on part of the government, who feign help and understanding, but at best, distract and at worst, conspire to act in violence.5 These are fatalistic films, possibly eschewing the label of “political thriller” because there’s nothing that thrilling about a story where you know the ending. One of these, of course, is fiction, and the other is based on something very true and very real. At the time of its release, Missing won the Palme D’or but faced an uphill legal battle in the States. I fell down a little wormhole of reading about the demise of the political thriller — it moved to television, Trump killed it, “Civil War is a political thriller.”6 Possibly all of the above, who knows.

To me, the demise of the genre is reflected in the end of Missing and the reviews of The Stars at Noon — that these things that happen to these people abroad, who learn something or see something, regardless of their political affiliation or whether or not they existed, wouldn’t have happened if they weren’t there in the first place. Ed feels this towards the start of the film: why isn’t his son living in America? what is his son’s job, exactly? why do he and his wife play-act as poor when they could have a car in beautiful New York City? It’s a tedious, uncaring point of view, one reflected in structures of power, the same point of view that looks out onto carnage — piles of bodies, hidden away in giant morgues or left out on the street or in mass graves, more visible now than they were in the 1980s — and says, these people should have done something different if they wanted to live, as if wanting to live is conditional and not a right.

The “why don’t they hang up on him” of it all with Chotiner ignores the very simple principle that most of the people who speak to him are obsessed with hearing themselves talk and cannot think forward in time enough to consider a reality where they might be made into complete fools.

If nothing else, it’s a solid reminder that these are two of the greatest American actors we have.

I like all three of them with minor caveats.

I admittedly care less about the fate of the British oil salesman — the novel makes it clear that he is some kind of agent, or moron, or has some involvement with what’s happening, and while I do not root “for” the death of a fictional character, it is loosely compelling to me that all these reviews are like SHE’S SO ANNOYING and leave him beside in the dust. In many ways, this is why Joe Alwyn was ideal casting.

Wrong, Civil War is a video game, including cut scenes.

Great as always!!!!!!!! Gavras' "State Department Trilogy" (Z, State Of Siege, Missing) and (maybe to a lesser extent) Stars At Noon feel as though they are classified as political thrillers because we as Americans cannot comprehend these stories being told for any other purpose, especially when they all have such profoundly bleak endings. When similar true stories are told on the domestic front, a la Dark Waters, The Insider, Erin Brockovich, they're almost always considered dramas, which then go on to win big awards. Those American films all have happy endings-- the bad guys get exposed!! Gavras shows what these other films do not, which is that exposing the bad guys doesn't actually bring them to justice or enact meaningful change in the world.

There's something to be said about the fact that Missing and State Of Siege both received serious pushback from the state department-- State Of Siege was withdrawn from the AFI festival in 1971, and Missing was pulled from US distribution for 33 years as a result of a highly calculated, utterly fraudulent lawsuit by former ambassador to Chile and death-by-hanging-at-the-Hague deserver Nathaniel Davis. That these films were fought against tooth-and-nail by the US State Department, despite the United States' ostensible commitment to free speech, meanwhile the same State Department milieu goes on to praise films like Brockovich and Insider, speaks volumes towards the films' ideological and artistic commitments, even if tackling the same subject matter (I say this as a great lover of all three of the American films I mention).

American films that deal with the crimes of the deep state almost always have to be fiction (Blow Out, Three Days Of The Condor), or else so fantastical as to otherwise be fiction (JFK), or else so neutered and artless as to be meaningless (That Jeremy Renner suck-fest about Gary Webb, R.I.P.), it's a sad state of affairs, but I think it speaks a lot to the lessons the United States Government learned from the Nazis, as well as what the actual "War" part of the Cold War was.

I think the sniveling diplomat you mention, or one of them anyway, is the one played by David Clennon, whose role in this movie tickles me greatly given his IRL leftist credentials. Check out his almost comically based IMDb bio.

I love (hate) the recurring flashbacks to the evil Texas guys barbecuing as they talk nonchalantly about their work moonlighting as coup consultants. The structure of this movie, the Lemmon of it all, is pretty conventional as you say, but that conventionality combined with the explicit and implied details make it so viscerally upsetting.