You’re reading Fran Magazine, a blog that used to publish on Tuesdays but now publishes on Wednesdays and basically no one noticed. This issue is for paid subscribers, but free subscribers will get a taste of the fun because it’s a good one. A paid subscription only costs $40 a year, the same price as a shirt that’s on sale.

The big Bernstein book of secrets

Back when I used to write about classical music for The Awl, I made it a habit to read a big book of nonfiction about classical once a year. This was always a fun, escapist thing to do, a reading activity that pulled me out of contemporary fiction and celebrity memoir into the world of biography and historical analysis. I learned so much about Berlioz and Dvorak and Prokofiev and Shostakovich, to name a few, and then when I started grad school, I fell off with that whole thing, pivoting, instead, to reading one giant classics a year (something I’ve yet to complete this calendar year, though Middlemarch sits idle by my bedside table). Since the Maestro of it all, however, I have had a newfound interest in Leonard Bernstein. Actually, that’s a lie. In the late summer of 2020, before we knew what was and wasn’t kosher to go do, Blythe, Harris, and I went to Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, which is where Bernstein was buried. I knew that Bernstein was this big New York figure—the street on which I see all of my NYFF films each year is literally Leonard Bernstein Place—but visiting his grave, adorned with both fresh flowers and stones, made me feel something new about him, a tender connection, I guess, if I can say something like that.

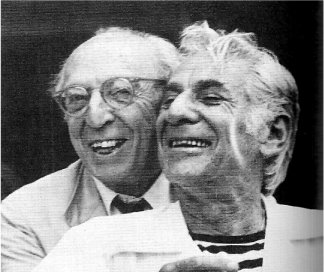

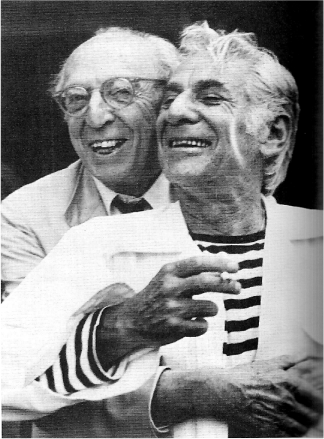

Earlier this year, I picked up Nigel Simeone’s The Leonard Bernstein Letters which has taken the place of my giant composer biography. It is an edited collection of Bernstein’s correspondence—so not all of it, but a lot of it—over the course of his life. It is a monstrous book, some 600 pages, and though I am only 100 pages of the way in, I am finding an unlikely (or perhaps likely) hero emerging: Aaron Copland.

I have known Copland’s work almost my whole life, and it’s possible I am more familiar with his work than I am Bernstein’s. Copland’s music is omnipresent in American life: you’ve heard it without realizing.

Copland himself was eighteen years Bernstein’s senior, though they died mere weeks apart. I had always known that Copland was kind of a mentor to Bernstein, but the letters between them give way to an intimacy and a humor I can’t help but feel warm and sentimental towards. The pattern of their correspondence goes a bit like this: Bernstein, still in his teens, will have some ego-driven meltdown, and Copland will talk him down. It’s very sweet and very, dare I say, relatable. Consider the following from 1938:

Dear Leonard,

What a letter! What an “outburst”! Hwat1 a boy! It completely spoiled my breakfast. But it couldn’t spoil the weather, so thank Marx for that. The sun has been shining in a way to defy all wars and dictators, and there’s nothing to be done about that.

[…] As for your general “disappointment” in Art, Man and Life, I can only advise perspective, perspective, and yet more perspective. It is only 1938. Man has a long way to go. Art is quite young. Life has its own dialectic. Aren’t you always curious to see what tomorrow will bring?

Of course, I understand exactly how you feel. At 21, in Paris, with Dada thumbing its nose at art, I had a spell of extreme disgust with all things human. What’s the use—it can’t last, and it didn’t last. The next day comes, there are jobs to do, problems to solve, and one gradually gets inured to things. At my advanced age (37) I can’t take a letter like yours completely seriously. I’m glad you wrote it, if only to let off steam. Write some more!

[…] I hope you’re coming to New York soon. I always enjoy seeing you.

Always,

Aaron