Three movies about hating your one friend and one movie that is about something else

Fran Magazine: Issue #121

📝 Thanks for reading Fran Magazine, a biweekly blog by Fran Hoepfner (me). The way this works is that Wednesday (regular) issues are free for all and Sunday (dispatch) and reread diary issues are for paid subscribers only. Consider subscribing or upgrading your subscription for access to more Fran Magazine, and feel free to follow me on Instagram or Letterboxd. 📝

September announcement

As mentioned last month, this September… Mervyn May… continues! Instead of weekly discussion posts, there will be one big discussion post at the end of the month about the second book — the aptly titled Gormenghast — in Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy. At the end of October, we’ll discuss Titus Alone. Yay!

I’m always mad at my one friend

When I was in grad school, I was obsessed with an invented genre of my own making called “I’m always mad at my one friend,” wherein the central character of a novel (or film, or TV show, whatever) develops an intense love and hatred and obsession with their close friend. Sometimes this is accomplished at a level of prestige — say, The Great Gatsby or the Neapolitan Quartet or Heat or The Social Network — and sometimes this is accomplished at a level of bad where the central text fears to engage with the actual complicated emotions that come with longterm or obsessive friendship. “I’m always mad at my one friend” can otherwise transcend traditional genre: The Talented Mr. Ripley is “I’m always mad at my one friend” and a psychological thriller; The Awful Truth is “I’m always mad at my one friend” and a romantic comedy (the exes/lovers here also being, in a way, friends).

Most recently, however, I have come to discover something that only I would realize at this stage in my life which is that a number of music documentaries are, in their way, “I’m always mad at my one friend” texts. As I have come to self-define as a “music idiot” — with regards to compositions made post, like, 1945 — most everything I have come to learn about contemporary music1 I’ve learned from music documentaries that I watch for either work or pleasure. In turn, I have absolutely no skill at gauging whether a music documentary is “successful” — all I need to believe for the duration of the runtime is that the band or musician I am watching is the most important one on earth. The Bee Gees documentary on HBO from a few years ago successfully did this. Get Back also did this.2 The classical music documentary I saw about female conductors at Tribeca last year did not do this: those women are always mad at their one, uh, glass ceiling, idk.

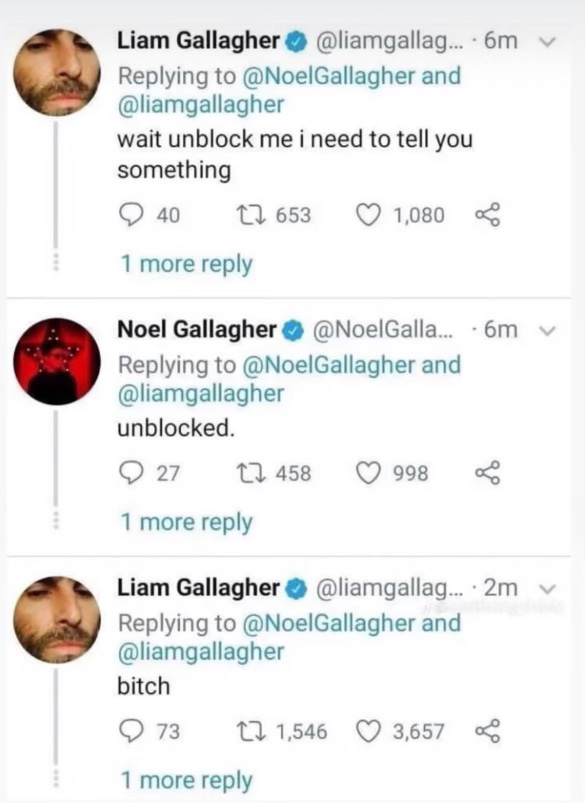

When rumors of the Oasis reunion started to trickle through two weekends ago, I struggled to understand what exactly had held up Liam and Noel Gallagher from making music the past decade or so. I knew the now-infamous Matty Healy quote about “being in a mard with your brother”3, but I didn’t really understand what was happening. A cursory Google search of “what are the Gallaghers mad at each other about” didn’t really shine any light. Liam kept getting laryngitis and then Noel would have to step in? I asked Phil “They don’t, like, really hate each other, do they?” and he looked at me like I was a child and went, “uhh, yeah, they do,” and then when I looked like this, he added, “but they probably still have to see each other at Christmas.”

Supersonic, the Mat Whitecross-directed Oasis documentary that we were both sure came out before 2010 but actually came out in 2016, is not a very good movie, nor does it successfully articulate that Oasis is the most important band of all time. There’s far more of these guys saying stuff about each other over animations or repeated footage of them on a tour van than there are scenes of them interacting with each other. But it’s a great “I’m always mad at my one friend” text, eager to depict the ways that the Gallaghers also quite essentially do need each other and rely on each other to make their band good. While other members of Oasis prove themselves disposable, the second one of the Gallaghers — usually Noel — quits or walks off, the whole thing crumbles under the weight of the other brother — usually Liam — not wanting to do it without his sibling. More palpable than the disdain the brothers grow to have for one another are their efforts towards love and understanding, only to be constantly rebuked by each other in the name of partying or rock ‘n roll or ego or whatever. “Who should sing Wonderwall on tour?” — a question I’ve seen floating around since their reunion was announced — is the ultimate execution of what motivates and frustrates these two.4

From Supersonic, we watched Dig!, Ondi Timoner’s documentary about the simultaneous rise of The Brian Jonestown Massacre and The Dandy Warhols and the ensuing rivalry between the two. Phil, Harris, Ly, and I went to see The Brian Jonestown Massacre a few years back at Brooklyn Steel (?); at the time of going, I knew nothing about their music and went under the guise of “maybe they’ll all yell at each other on stage” (they certainly took shots at each other, but seemed more annoyed with the audience). The Dandy Warhols are a little more familiar to me, because I have seen commercials that use “Bohemian Like You” and most crucially, I was a Veronica Mars viewer.

Dig! had been back of mind since I saw TBJM, and when Caroline and Geoff saw it earlier in the year, I knew I had to make it a priority. The “deal” with The Brian Jonestown Massacre is that their lead singer and musician, Anton Newcombe, is an insane multi-instrumentalist surrounded by vaguely affable druggies who are mostly happy to take direction and verbal abuse from him because they recognize that he is a genius. Occasionally this spills over into on-stage or in-house conflict, but every tends to respect that Newcombe is some kind of genius and worth bolstering as the frontman of this band. The Dandy Warhols, on the other hand, are a much more conventional “band,” e.g. there are four of them and not, like, 9-14 depending on the day, led by Courtney Taylor-Taylor5 who has a classic type of frontman, pretty boy vibe. The Dandy Warhols love The Brian Jonestown Massacre and recognize their genius for all its worth; The Brian Jonestown Massacre, on the other hand, tolerate The Dandy Warhols, who they sometimes like as guys but mostly find to be annoying and not that talented in comparison.

Here, “I’m always mad at my one friend” gets kind of transmuted into “I’m always mad at my one other band”: The TBJM need The Dandy Warhols to maintain a type of legitimately indie, legitimately rock ‘n roll status whereas The Dandies sell out doing commercials, whereas Courtney Taylor-Taylor needs someone like Anton Newcombe to inspire him to write better music while actually just continuing to write bad music. At one point, during a photoshoot, The Dandy Warhols use The Brian Jonestown Massacre’s house so they can feign a dirtier, yuckier lifestyle than any of them are actually committed to. Later, Anton Newcombe sends The Dandy Warhols shotgun shells with their names on it. At one point in the film, someone points out that Anton Newcombe is probably incapable of having any other kind of job; he was always going to be — and is meant to be — a musician in a rock band. Comparatively, one of The Dandy Warhols is now a realtor.

After that, we watched Vox Lux. Vox Lux is not an “I’m always mad at my one friend” text. Who is she mad at, her sister? Mostly Vox Lux is mad at the United State of America (real). Over the next few months, you are likely to see a lot of Vox Lux revisionism from people on Twitter, arguing that not only is Vox Lux good but that it was always good. Don’t fall victim to this. Upon rewatch, I was relieved to confirm that Vox Lux is basically bad but also undeniable. It is “aging well” in that our country is only more fascist and pop music lends itself to increasingly violent spectacle; it is “aging poorly” in that no one from Staten Island sounds like that and no one in the movie sounds the same on a scene-to-scene basis. It is better composed than a number of other movies — I’d agree, for instance, that Corbet is a better director than he is writer — but that does not mean the overall effect is “good.” It is just interesting, which is fine. When Caroline and I saw it at Film Forum in 2018 the same day as Santa Con (life rocks!), we were the youngest people in our showing by a good two decades and everyone else was sooooo mad, like, we couldn’t stop laughing!

A bad mood settled into the apartment upon concluding Vox Lux, and Phil said, “Can we watch the first twenty minutes of Popstar?” which is like saying, “Okay, only one bite of cake!” Obviously we watched all of Popstar. I’ve seen this movie too many times — there’s lore we can’t get into here and now, but IYKYK — the Lonely Island’s mockumentary works in part because they recognize that the actually compelling and best part of most music documentaries is the “I’m always mad at my one friend” aspect. The film loosely details the rise of the fictional Style Boyz (played by the Lonely Island members) through which only “Conner4Real” (Andy Samberg) breaks through, leaving the other two members to fall subservient or quit entirely.

What works well about the movie besides the fact that it is joke-dense and an especially good showcase for Tim Meadows (<3) is that the film takes the form of the modern pop concert documentary while including the “I’m always mad at my one friend” emotional thru line that has otherwise escaped the modern concert doc. Popstar is essentially a parody of the genre, but I think it is most in conversation with Wicked director’s 2011 Justin Bieber documentary Never Say Never. If you haven’t seen Never Say Never — I don’t really care about how you feel about Justin Bieber — it is kind of an undeniable entry in the genre (along with the Katy Perry concert documentary Part Of Me) but it does not have an emotional rivalry the likes of “I’m always mad at my one friend” because Justin Bieber isn’t mad at anyone. The modern pop documentary is largely unsatisfying because if these people are mad at each other, they’re keeping it off camera for PR and/or legal reasons. Part Of Me, the Perry doc, is good because she’s mad at Russell Brand — who isn’t! — and has a scene where she basically does the Michelle Williams gif from Fosse/Verdon. Everything I’ve seen either parts or all of — the One Direction documentary (sorry Clare), the Billie Eilish movie, the Ed Sheeran doc, whatever — these are all largely forgettable not because of the music within them but because they are more compelled to explore things like “mental health” than they are the ways in which people in pop music are forced to compete with each other constantly. Even the Taylor Swift film Miss Americana leaves out most of her ire for those in her industry that aren’t that DJ who touched her ass and Donald Trump. I’m sorry — this is boring. One of the most thrilling aspects of Swift’s music is that she is so mad at everyone all the time, but is only willing to take shots in overwritten lyrics rather than just say what she means. This allows her to maintain a kind of “graceful winner” status, but she’s never really been graceful and her winning came at a high cost.

Popstar works in part because it explores the way in which these pop acts exist within a context of each other — what does it mean, for instance, when your opener starts to outsell the main act? — and because something like “I’m always mad at my one friend” fuels creativity and imagination, forcing its subject to confront relationships, jealousy, obsession — professional or sexual or some combination of the two — and intimacy, most of which is not actively present in contemporary pop music minus maybe the most recent Shakira album about her divorce (but that’s a divorce album, not responding to friendship). Maybe there’s an innate personal politic in music that can only be represented through the framing of something like film — no one can just say these things in the context of the world of music, or at least not like they used to. The participants of Dig! purportedly found most of the events in the film exaggerated or not as important as they appear in the film’s narrative. In the reality of “I’m always mad at my one friend,” the simplicity of the statement doesn’t feel so clear cut or obvious or even apparent as a projection of anger, if that is the root of it. We make excuses or we storm out or we do something somewhere in the middle of these things. Not to go full “looking back in anger,” but this type of ire feels only apparent in retrospect, not present, when the walls around the moments have gone black and the screen flashes.

Spencer Williams, a poet from my grad program, once begged me to stop calling it “contemporary music.”

A question: Is Get Back an “I’m always mad at my one friend” text? Certainly much of the Peter Jackson-directed, yassified Beatles documentary is full of “I am always mad at my one to three other friends and/or one of their girlfriends,” but I’d argue the Beatles are not propelled nor motivated by whatever interior rivalries existed in their band. Mostly Get Back is about aging out of your friends — much more tragic — and kind of a “one last job” piece. Where are those eight more hours of footage that PJ keeps threatening to release? I’m ready to watch them.

As annoying as I find Healy, I am grateful to have learned the word “mard” which stems from “mardy” — for spoiled — from him.

It should be Liam.

If I think too hard about this name, I get actually mad that it’s nothing something I made up myself.

Vox Lux obviously a mess top to bottom (albeit a movie that passes my “lmao what” test in that it made me go “lmao what” multiple times), but I was baffled at the climactic performance scene because they have Natalie Portman wearing these 2” heeled black Chelsea boots like I wore at my retail job at the time because I had to be on my feet 8 hours a day, like truly what are best identified as commuter shoes, to the point that I wondered if she had forgotten her correct shoes back in her trailer and this was sort of a Starbucks cup in Game of Thrones situation because in no universe would these be considered stage wear for the type of pop star she’s seemingly meant to embody. I love that I’ve been stewing over this for nearly 6 years.

what made me laugh the most about supersonic is that they both, liam out of some weird polite appreciation for his brother’s savant musicality, noel out of an inability to concede his approach to fame is wrong, are incapable of admitting that oasis was only ever huge because they were hot and cool. though liam is the instigator he is right: looking cool and doing drugs is the backbone of the whole enterprise, and if you let noel take it over with the weird slow poetry, it falls apart. the central antagonism seems to be that liam is hot and that makes noel mad. but if the movie was about what rockstars are really all about, it would be dismissive of the band’s artistic contributions. someday they will invent a way to make music docs that balance these ideas but it is not the time for that.

always mean to watch the billie one because i hear that in it she doesn’t know who orlando bloom is until someone says “that’s the guy from pirates” — me

1d doc only memorable because of when harry gets really annoyed with niall for wanting to wear a mask as a novelty in japan. like i don’t want to be trapped in a car with any of those jokers either. zayn was right to leave